The India-Japan nuclear agreement would be an international disaster. We must stop it. -Nuke Info Tokyo No.169

The India-Japan nuclear agreement would be an international disaster. We must stop it.

KUMAR SUNDARAM,

Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace (CNDP)

It’s important to realise that the nuclear deal between India and Japan is much more than a bilateral agreement, and it must be opposed as we approach the 5th year of Fukushima.

The India-Japan nuclear agreement would be an international disaster. It would rehabilitate the global nuclear lobby, which is facing its terminal crisis after Fukushima. They are aiming to use the toothless safety laws and corrupt politicians of India, and the general political apathy for the lives of the poor and the environment in the country.

The agreement essentially does 3 things:

1. It provides a safe home in India for the international nuclear lobbies, where they compensate for their terminal global crisis post-Fukushima and regain the financial health to bounce back globally later. The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2015 unequivocally highlights the terminal crisis resulting from the escalating costs of nuclear, the adverse popular perception, the more stringent safety norms increasing the costs and incubation periods, and a simultaneous growth in the efficiency and competitiveness of the renewable sector. The ‘renaissance’ that the nuclear industry has been talking about isn’t really happening anywhere else except India, China and a few other smaller Asian countries with limited nuclear plans. India has the largest nuclear expansion plans in the post-Fukushima world and the global nuclear industry is looking at it as an attractive destination with toothless safety norms and the general political apathy towards the lives of poor people.

The Japanese deal is essential for the reactor projects of the US and France to proceed on the ground as some crucial reactor equipment is manufactured only by Japanese companies. Another reason is that the two major US nuclear giants – GE and Westinghouse – have become Japanese owned companies.

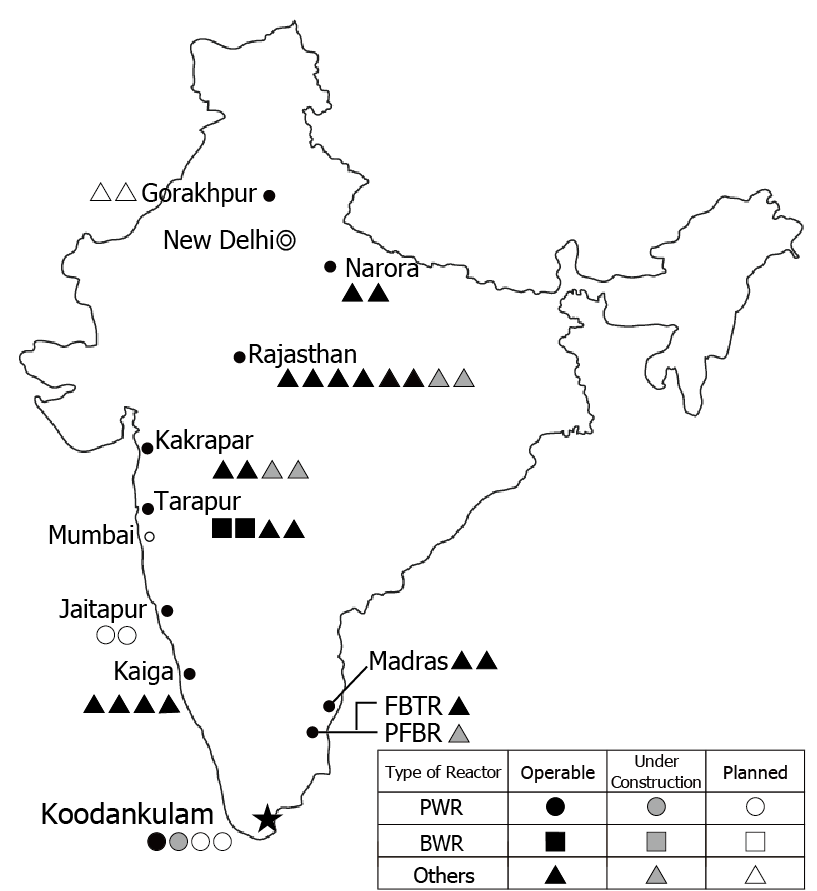

In immediate terms, the deal means 6 EPR reactors for Areva and 4 each for GE and Westinghouse. Japan will only supply crucial equipment and there are no turn-key reactor purchase talks so far, so the financial gain for Japan isn’t really all that big, but the US and France have been pushing Japan to conclude a deal with India asap, as has been reported in the media.

2. This deal implies a serious threat to the people of India, particularly the most vulnerable sections in the rural areas, whose lives and livelihoods are at stake. India is imposing these reactor projects at gunpoint against the wishes of the local communities, in ecologically fragile, geologically sensitive areas with dense human populations.

The people – tens of thousands of farmers, fisherfolk, women and children in these areas – depend on the local ecology for their food and livelihoods. These will be threatened both in terms of forced mass eviction for these projects with compensations only for the landed few, as well as the loss of traditional vocations for a larger number around the proposed project sites.

Nuclear energy has its own inherent insurmountable problems and the world has realised after Fukushima that nuclear safety is an oxymoron – a dynamic concept which the industry has to keep chasing, and it cannot afford to fail as nuclear accidents inflict irreversible and long-term damage. But the nuclear industry has become much more risky in India owing to the totally non-transparent nuclear sector with scant regard for independent scrutiny. India is perhaps the only country after Fukushima which has proposed a weaker nuclear regulator to replace its already weak and toothless nuclear safety monitoring body. The government is making every effort to do away with already weak legal provisions to hold the nuclear suppliers liable in case of accidents. The larger bureaucratic apathy and corruption, more appalling when it comes to deliver things to the poor, can be relied on for unaccountable operation of reactors and dangerous mismanagement of potential accidents.

3. The nuclear supply from Japan to India creates a bad precedent for nuclear disarmament. It practically rewards a country which conducted nuclear tests, defying sane advice from within and outside, at a time when the world is looking towards measures to make the nuclear commerce regime more stringent as the number of potential proliferators increases.

India conducted nuclear tests in 1998, without any immediate threats or provocations, under the right-wing government of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to boost its self-image. The pursuit of macho-nationalism is also linked to an increasing Hinduisation of India, leaving the minorities insecure and secular voices stifled. The same BJP is in power again, under a more hard core leader and with a brute majority, and the rising militarism in India could spill over to South Asia. The region has two nuclear-armed nations and any small conflict, often used for domestic political purposes, can escalate into a nuclear exchange.

Apart from the above specific negative implications of the deal, the larger context in which India-Japan relations have taken a decisively militarist turn should also not be missed. The first beneficiary of PM Shinzo Abe’s policy of re-starting military exports to foreign countries is going to be India, which will buy the Shin-Meiwa US-2, the amphibious ‘rescue’ aircraft. The joint exercises in the Indian Ocean by the Indian and US navies have caused anxieties in Pakistan and China and are seen as a part of the larger US design of propping up a Japan-India axis to counter China in the region.

India’s nuclear future at the crossroads

The nuclear deal with Japan also comes at a time when the nuclear energy plans of India are at an important juncture. The new Indian PM – Narendra Modi – belongs to the Hindu-majoritarian BJP, which places strong nationalist pride both on nuclear weapons and nuclear energy. During his recent overseas visits in the last eighteen months to the US, France, Australia, Mongolia and Japan, Modi has strongly pursued nuclear commerce agreements. He has abandoned even the minimum reservations that his party used to raise when it was in opposition for ten years before him.

India’s newly appointed Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Shekhar Basu, almost taking a leaf from Modi’s zeal for nuclear power, started his sting with a press conference where he announced that the foreign nuclear suppliers should not be made liable for any accident.

The Indian law, the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010, provides for a ‘right of recourse’ against the nuclear suppliers in case of an accident to the state-owned operator Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) under Clause 17(b).

The clause was introduced under pressure from Parliament and civil society by a reluctant Manmohan Singh government. At that time there was a public outcry on liability, following the June 2010 Bhopal judgment that let the accused go almost scot-free. This led to a sensitive debate.

Although the Act capped the total liability at a ridiculously low amount and was criticised for its complicated procedural stipulations, it provided for a very limited hook on private suppliers – both foreign and home-grown.

Attempts to dilute and circumvent the liability norm started soon. These included making supplier culpability dependent on an explicit mention of the liability provision in the bilateral contract between the supplier and the operator.

In addition, the Indian government limited the product liability period to just five years under the Nuclear Liability Rules, 2011, designed to guide the implementation of the 2010 Act. Eminent jurist Soli Sorabjee termed the Rules “ultra vires” (beyond the powers) of the Act and going against its spirit.

In his last foreign trip as PM, when Singh went to the United States, he offered “as a gift” a reinterpretation of the liability law. According to that reinterpretation, the operator has the option of not exercising its right of recourse against the supplier. He assured Obama that the public-owned Indian operator will not sue suppliers.

Evidently, even this failed to assuage companies such as GE and Westinghouse. They were uncertain about future Indian governments abiding by such a promise, especially in the wake of public pressure that would follow any big nuclear accident.

The foreign corporations have also been opposed to the Indian law as it is a departure from the CSC, which they want the world to adopt as an international template. Ironically, India rushed to sign the CSC in October 2010, soon after it enacted the domestic law. It then started citing that as a reason to amend the Parliament-mandated law.

At that time there were fewer CSC signatories. Only in April this year has the Convention entered into force. India had an opportunity, as an attractive investment destination for the nuclear sector, to actually lobby for amendments to the CSC to ensure adequate liability for people in developing countries. Japan’s signing of the CSC gave it the required legal status and now it has become a weapon to push other countries to exempt suppliers from liability.

Koodankulam not working

Another announcement that the new AEC Chairman made was about Koodankulam resuming operation “soon”. The reactor near the southernmost tip of India, started two years ago with much fanfare and after brutal repression of local people who were opposed to the project.

Ever since its inception, the Koodankulam Atomic Power Project has courted controversy. The nuclear power plant, imported from Russia, has been a bone of contention between the government and the nuclear power lobby on the one hand and anti-nuclear activists, environmentalists and local villagers on the other since mid-2001.

Three and a half years ago, the backers of the project had scrambled to prove that nothing was more important and urgent than the N-power project to solve the power crisis in Tamil Nadu and other southern states. Protests were eventually scuttled and Unit 1 of the project was commissioned on 22 October, 2013.

After being commissioned, the plant failed to function at full capacity for many months and was declared commercially operational only on 31 December, 2014. In these 14 months, the reactor shut down 19 times due to tripping, and there were three maintenance outages.

Tripping is common at nuclear reactors undergoing tests. But in Koodankulam, their frequency is very high. At 14 trips during the plant’s 4,701 hours of operation until now, the trip rate is 20.8 per year – way ahead of the global average of 0.37, according to a World Nuclear Association report.

The 10 best-performing reactors had a trip rate of a mere 0.25. The same report underlines an average 1.5 days of loss of productivity per trip globally. In Koodankulam, the average is 6.5 days – that’s nearly a week lost.

In its two-year existence, the Koodankulam reactor is yet to achieve the minimum benchmark – operating continuously for 100 days at 100 percent capacity. The plant operated below its capacity for 134 days between 10 December, 2014 and 24 August, 2015, and a total of 124 days at full capacity, but not continuously.

Negotiations for the India-Japan nuclear agreement must be terminated

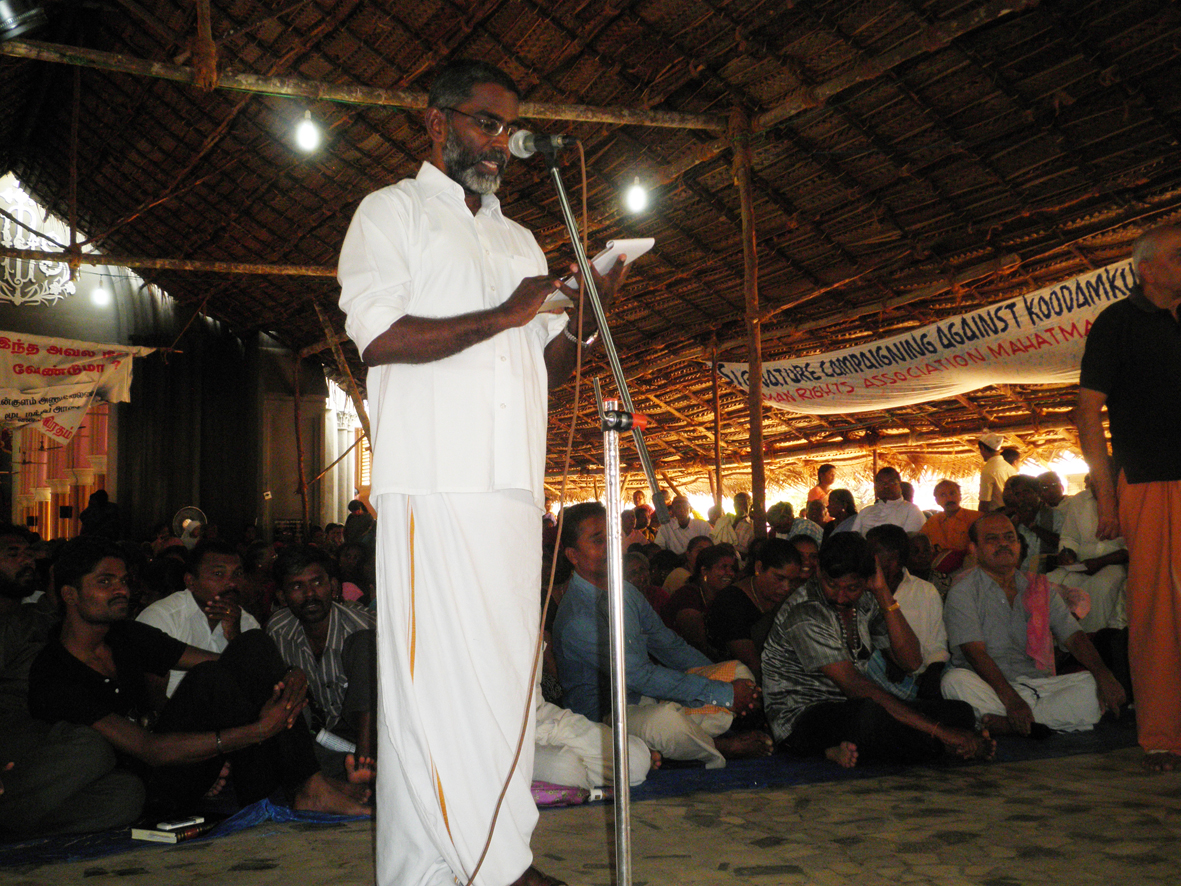

In India, local communities and activists are protesting against nuclear plants being set up on their land. They have raised a wide array of issues – damage to livelihoods and the environment, inherently unsafe nature of nuclear energy, its adverse economics and undesirability for India’s energy future, shoddy safety regulations, and an unaccountable nuclear industry.

Add to this the global shift away from nuclear power post-Fukushima that India stands to miss due to its nuclear obsession.

At a time when the world and citizens of South Asia should actually be asking for more restraint measures and a nuclear-free zone in the region, this deal would legitimize India’s nuclear weapons and bring India and Japan closer in a militarist framework, purportedly to counter China as per the US strategies.

All peace and democracy loving people across the world must demand scrapping of this nuclear agreement between India and Japan. The two Asian countries should instead focus on alternative energy technologies, learning lessons from Fukushima, and focus on reducing and eliminating nuclear weapons in the 70th year of Hiroshima.